English 931: English Authors after 1800

Fall 2010

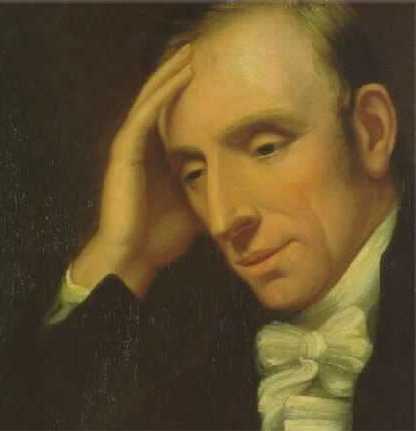

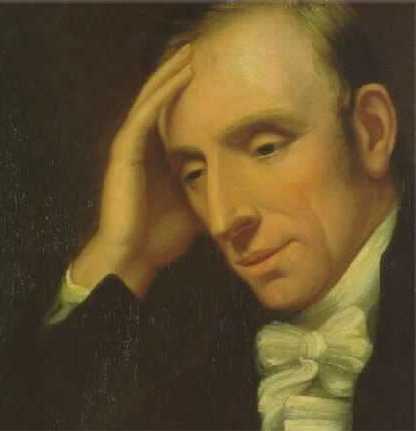

William Wordsworth

Stephen C. Behrendt

319 Andrews; 472-1806

office: 10-12 TR, and by appointment

Email Stephen Behrendt

Symposium Project: Details, Suggestions, Instructions

Project Timeline:

12 October (Tuesday) Submit (in writing) tentative topic and thesis

26 October (Tuesday): Submit full prospectus, with preliminary annotated bibliography

7 December (Tuesday, our final regular session): Submit complete project and all related materials

For 12 October: Thinking about your topic and thesis:

1. What general subject area within the life, works and times of William Wordsworth – and his subsequent continuing presence within, and influence upon, British poetry – is of greatest interest to me, either (a) in its own right, or (2) in relation to my graduate career plans, including my MA of PhD thesis?

2. What do I already know (1) that interests me particularly, (2) that gives me a strong starting-point for a “new” project, or (3) about what has been done in (and around) this subject area?

3. What do I need to figure out in order to start? What questions do I need to ask? What strange, odd, inconsistent “facts” (or assumptions) have drawn me to this particular subject area?

4. What has already been done by others that may (1) help me to frame up my subject, in terms of either “theory” or “data,” (2) supersede what I think I might like to do, or (3) get in my way?

5. What resources will I require in order to pursue this project and this subject area? Books? Journals? Microform or other archival materials? Online resources, including textbases (like ECCO, Google Books, Open Library, Project Gutenberg, JSTOR, etc.)? Visual and other non-print materials?

6. Are these resources available at UNL? If not, how can I get them (or get to them) in time to use them in my research?

7. I suggest that you spend a lot of time simply tossing these questions about in your mind and considering any and all answers (however tentative) at which you arrive. Your goal for the 16 October deadline is to come up with as specific a topic as you can manage: not a generalized swath of an idea (e.g., Wordsworth and women) but something genuinely specific.

Poor: “Wordsworth and poetics”; “Wordsworth and politics”

Good: “Wordsworth’s treatment of ‘ordinary’ language in the Lyrical Ballads demonstrably forced his contemporaries to reassess aesthetic criteria for evaluating poetic diction.”

“Wordsworth’s implicit linking of poetry and ‘morals’ anticipated the activist politics of contemporary poetry of social commitment.”

8. You may find it especially useful to think of this part of the project, which I want you to submit to me in writing on 12 October, as involving two parts:

1. Your actual tentative thesis sentence.

2. A brief paragraph that states, more broadly, your general idea, how and why you arrived at it, and what you expect to discover or to demonstrate. The paragraph should “situate” your thesis by providing some additional context for that thesis. The paragraph may (if you wish) indicate briefly the relation of your proposed project to your personal career and/or graduate school plans and objectives.

For 26 October: Preparing a full prospectus and preliminary annotated bibliography.

1. Have a look at my “instruction sheet” for preparing a dissertation (or thesis) prospectus. While a thesis or dissertation is of course a much more ambitious and elaborate project than a symposium essay, the principles involved in preparing a prospectus are much the same as those that guide shorter projects like graduate course projects and essays, articles, and chapters that you will prepare for publication. So try to internalize my instructions and then apply them to what you are thinking of doing with your own project. Even when what I have written in those broad instructions is not immediately or entirely applicable to your own project, you may at the very least get some sense of how to formulate a blueprint and methodology for yourself that will be better suited to the work you are doing – especially if your primary area is not one that we typically consider to be grounded in – or focused upon – research-based “literary/cultural scholarship.”

2. Having thought about all this, begin expanding, revising, or even wholly rethinking that original paragraph (and thesis) that you submitted on 12 October. The Prospectus is really both a blueprint and a “plan of action.” That is, by now you should have thought through all those issues involved in the questions above, and have begun to make serious and measurable progress toward identifying and pursuing potential or tentative “answers.” Perhaps (and this is very likely) you will have in fact generated more questions and identified additional problems – with critical or theoretical paradigms, with research resources, with methodological issues, etc. – and you should now address these in your prospectus, where you should also indicate how you intend to deal with them.

3. Some questions that will probably emerge at this stage. What have you had to alter in terms of your thesis itself, the larger literary or cultural context in which you wish to situate your work, the critical or theoretical paradigm(s) or methology(ies) you wish to employ, or the resources you need to consult? How will you accommodate these changes to your overall plan? How – and why, or why not – will the answers to these questions require you to reformulate your thesis or your overall plan of action?

4. Really, the point of a prospectus (you will find this is equally true, later, by the way, when you propose a book to a scholarly or a commercial publisher) is to situate your subject within the current broader discourse of your field, explaining how it relates to work that has already been done (and identifying particularly important related or previous work), how and why your own work differs from that previous work (confutes it, reformulates it, takes it in a new and previously unexplored direction, etc.), and why your work therefore contributes meaningfully to knowledge (and intellectual conversations) rather than merely restating old and familiar truisms.

5. The Annotated Bibliography. This is simply an annotated record of your “reading list.” I suggest keeping annotations (which may be as brief and as minimal as you wish) simply to keep track of what you consult, so that you will know where you have found things and have some sense of what ground you have covered. This is not a “Works Cited” list; list everything you consult, even if your “annotations” run no more than a few words. This is not just proving that you have done your homework (although it does serve that purpose); rather, it has to do with mapping the territory, just like a surveyor, so you’ll have a record of where you have been and where you have not been. Sometimes the blanks are as meaningful – and as diagnostic – as the fully mapped spaces.