English

180:

English

180: Introduction to Literature

English

180:

English

180:

Introduction to Literature

Spring Semester 2008

Stephen C. Behrendt

319 Andrews Hall

phone: 472-1806

office: 1230-130 TR

and by appointment

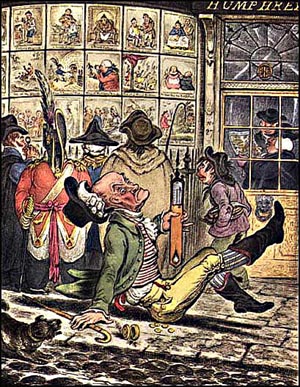

James

Gillray, Humphrey's Shop

Information about this Course

Course Texts: Portable Literature: Reading, Reacting,

Writing. Sixth Edition. Ed. Kirszner & Mandell

Mary

Shelley, Frankenstein

Aims of this course:

The primary aim is to help you gain greater confidence and self-awareness with reading in general — and with reading “literature” in particular — so that you will become a more effective reader, no matter what sort of writing you are reading. In order to accomplish this objective, we will read and discuss a broad variety of texts.

In fact, one aim will be to help you get a better sense of just what it is that we mean by the term “literature.” “Literature” has probably never meant exactly the same thing to everyone at any given point in history, even within a relatively small social group of readers. Like any form of art, literature is always the subject of controversy and disagreement, precisely because it is made up of a dynamic and continually evolving body of materials.

Indeed, about two hundred years ago, during what literary historians usually call the “Romantic” period in Western culture, many writers and thinkers argued that “literature” was not a body of writings at all but, rather, an interactive process that involved not just individuals but whole communities of readers, all of whom were expected to be familiar with many “texts” and also to be actively involved in interpreting them within the broad parameters of social and cultural activity. In that sort of a cultural community, literature (and art) occupied a central place in the society, rather than being relegated to the periphery, as they often are today. The “hottest” ideas were debated energetically not just in the streets but also in all the various forms of writing (and other artistic media) — and both the artists and their audiences were almost always able to assume that every member of this group activity was familiar with the issues and with the ways in which the various literary and non-literary artistic forms “worked.”

Within the last twenty years or so there has been a great deal of new interest in the ways in which the various forms of writing function within cultural communities. These “forms of writing” range widely, and they can include everything from familiar conventional literary works like formal poems or deliberately intellectual novels to song lyrics, graffiti, and even forms that are not written down at all (like “poetry slams”). They also include other types of formal writing like religious texts, history writing, journalism, editorials, and the drama, to name only a few.

So one more aim of this course is to help you better to appreciate that while reading is necessarily a very private activity (most of us read alone, silently, just as you are doing as you read this sentence), that reading activity is never entirely separated from the community to which you belong and to another community to which the author belongs (or belonged). Moreover, if you think about it, you will realize that a very great deal of this private reading that we do is actually closely involved with group activities and group identities: when you read your Bible or Koran, your family history, your fraternity or sorority information, your horoscope, you are participating in various types of communities in which all the other members understand the “language.” Those communities to which we belong, and whose values and cultural practices have shaped each of us, are also the communities to which we take back the results of our private reading, where we may choose to “try them out” on others. In other words, all texts are surrounded both by other “texts” and by a variety of contexts that result from who each of us is and from the experiences that have made each of us what we are.

The Bottom Line

Throughout this course we will be concerned with different approaches that we can take to texts. We will begin with the idea that we are all “general readers” — members of an academic community but not a highly specialized group of “literature specialists.” The questions we will explore are those that readers have often explored, and it is no exaggeration to say that most of those questions do not have what we might think of as “answers.” The study of art is not rocket science —— it is harder! We will try to remember in our work that what we do as readers is often affected by factors that lie outside each of us . Imagine trying to discuss Shakespeare’s sonnets (or Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, or Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein) on September 11, 2001, for example, and you may begin to appreciate the point. We have all learned to read in different ways and at different times and in different places. So each of us brings to our reading a whole lifetime of intellectual, cultural, moral, political, economic, and gender conditioning. No wonder that we may disagree on what any text (ANY text) “means.” Discovering the “meaning” of any text — or of any cultural phenomenon — is often a matter of narrowing down the possibilities by deciding among ourselves what it is NOT and then settling for the fact that we are left with a constellation of various, possible “meanings” that incorporate and represent our differing approaches and experiences as readers.

A Word about Procedures

We will work primarily through discussion. I expect you to contribute to these in-class discussions on a regular basis, and your contributions to discussion (or your lack of them) will be important to your course grade. While I hope to keep our class sessions relatively informal and not intimidating, I expect each of you to take very seriously the work that we will be doing, and to treat both the assigned readings and one another with respect at all times.

And another about Grades

On your course handouts — and on the course website at the “Course Writing Assignments” page — you will find information about the writing assignments and the grading standards for the course.

There will be two examinations, one at about the middle of the semester (and covering Fiction; 15% of your course grade) and another at the end (covering the entire course; 20% of your course grade). The examinations will be heavily grounded in the assigned readings and in our discussions about them, so if you fail to attend classes you will very likely fail the examinations – and probably the course.

You will write two brief papers, one each on the Short Story and on Poetry. Each paper will be worth 20% of your course grade.

Finally, you will be graded for your participation in classroom discussions. Discussion work will constitute 15% of your course grade. I expect you to attend all class meetings, and to come prepared to discuss the assigned readings for each session. To earn an A for the discussion component of the course grade, you will need to contribute in a meaningful fashion to discussions on a regular basis.

NO ONE will receive a course grade above a “B” who does not contribute to discussions on a regular basis, regardless of grades on examinations and papers.

NOTE: Your enrollment in this course constitutes your acceptance of these course requirements and grading expectations.

Students with disabilities are encouraged to contact the instructor for a confidential discussion of their individual needs for academic accommodation. It is the policy of the University of Nebraska - Lincoln to provide flexible and individualized accommodation to students with documented disabilities that may affect their ability to fully participate in course activities or to meet course requirements. To receive accommodation services, students must be registered with the services for students with Disabilities (SSD) office, 132 Canfield Administration, 472-3787 voice or TTY.