English

331: English Authors ---

English

331: English Authors --- Byron and Hemans.

English

331: English Authors ---

English

331: English Authors ---

Byron and Hemans.

Spring Semester 2005

Stephen C. Behrendt

319 Andrews Hall; 472-1806

office: 1-3 TR, and by appointment

Email Stephen C. Behrendt

Aim of this Course:

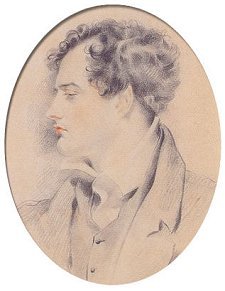

During the next several months you will get acquainted with the writings of the two most famous — and most popular — British poets of the first half of the nineteenth century. George Gordon Byron (better known as Lord Byron) and Felicia Hemans were both prolific writers who achieved great fame during their lifetimes.

Despite a notorious reputation for a disreputable lifestyle, Byron was the first great literary celebrity among British poets, the first whose personal life was as interesting to his readers as his poetry was. His lifestyle anticipated, in many respects, that of some modern rock stars, and it tended to offend and alienate a broad segment of the British public even as it attracted and energized another, usually younger, segment. His wrecked marriage, his well-known dalliances with women from all stations in life, his self-imposed exile from Britain, his association with writers like Mary and Percy Bysshe Shelley, his participation in revolutionary politics, and his untimely death at an early age all fascinated both his contemporaries and his successors, both in literature and in the visual arts, and both in Britain and throughout the western world. At the same time, his poetry seemed to many of his contemporaries to express a profound weariness with the world of the early nineteenth century and with all aspects of human experience, in part because Byron communicated over and over a sense that the "modern" world — and modern humanity — was irreversibly diminished from what it had been in some earlier and more "heroic" age.

Felicia Hemans enjoyed an equally wide reputation and influence, although it was very different from Byron's. She began auspiciously as a poet, publishing a variety of sophisticated and intellectually ambitious poems, sometimes anonymously; some of these anonymous publications were publicly judged to be of such high quality that professional reviewers declared in print that they were surely not written by a woman. She admired Byron and hoped to emulate in her works both his passion and his influence. Byron knew her work (and her popularity) well enough to express a sense of deep rivalry by referring to her in his letters as "Mrs. He-womans." Hemans did not do what so many women writers of the Romantic period did — begin with a volume or two of poetry and then turn to publishing novels. Instead, she continued to work in poetry, producing volume after volume until her own early death. Unlike Byron, however, Hemans was tied to "house and home" by family matters: abandoned by her husband, she was left to provide for her children, which she did through her writing, and which may be perceived to have had a real impact on that writing. By the time of her death, she was widely regarded as the "ultimate" woman poet, famous for a poetry that was widely judged to be delicate, sentimental, and thoroughly grounded in (and supportive of) what today would be called "family values." And yet this estimate of her and her work may not in fact do justice to the person and the poet that Hemans was.

We shall read widely in the works of these two poets, chronologically for the most part, both to become better acquainted with them and to examine the beginnings of "the modern world" as it began to take shape in the wake of the French Revolution and the defeat of Napoleonic France. We will read the poetry and prose of Byron and Hemans within the context of British culture, in other words, but we will also use their works as a means of getting acquainted with that culture itself and with the distinctly "modern" issues, themes, and preoccupations that followed the high tide of Romanticism that crested in these two writers. We will also consider the larger — and perennial — issues of celebrity, fame, and the nature and function of "popular culture," especially when that popular culture contains elements of a definable "counter-culture."

How we will do our work:

I want us to proceed primarily through discussion. I will lecture occasionally and briefly, but we will do most of our work in a conversational mode, augmented with a variety of supplementary materials drawn from the visual arts, music, theatre, history, and popular culture. We will subdivide at times to work in smaller task groups, on particular, focused projects. At other times, I will ask you to work (alone or in variously configured groups) to prepare presentations on diverse aspects of the course materials. Most of this will be relatively informal, in order to maintain the conversational nature of the course.

What I will require of you:

First, I will expect dedicated reading of all assigned texts, in advance of

class meetings for which they are assigned. I do not want to get into quizzing

to find out whether you have read things; that produces little more than bad

feelings on both sides. I anticipate having two examinations (a midterm and

a final), as well as a directed course research project. These nature and scope

of these may turn out to be negotiable, depending upon the enrollment and configuration

of the course. We will definitely have some presentations, as described above.

And (of course) course evaluations at the end.